A look down at the Morro Bay’s new sewage treatment plant’s treatment train — tanks, pipes, pumps and compressors — from atop the plant’s screen filtering platform. Sewage enters the plant and is piped all the way to the back and uphill, and then gravity moves it from treatment stage to stage.

Morro Bay’s new sewage treatment plant is largely completed and expecting to go online in early October, according to the project’s construction manager.

Steve Mimiaga, of Mimiaga Engineering, a subcontractor to the overall project management firm, Carollo Engineers, took an Estero Bay News reporter on a walking tour of the new facility, which is located above the terminus of South Bay Boulevard at Hwy 1.

Mimiaga said they’ve been running the plant through with the City’s clean drinking water since last March, testing the fittings, pumps and tanks, as well as the extensive system of monitoring and computer controls. They plan to do more testing this month, he said, and the plan, at this point, is to bring in raw sewage piped from the old treatment plant on Atascadero Road — on Oct. 4.

Mimiaga said they’ve been draining water out of a fire hydrant at the plant. “We are using a lot of water in a drought,” he conceded. “We’re using potable water for the tests, we have no choice.”

The plant site has been a beehive of activity since they broke ground in Spring 2020. But the past month or so, it’s been mostly deserted by comparison, signaling the end is nigh for the City’s biggest public works project ever.

The plant is a membrane bioreactor, with advanced micro-filtering, which when done with the treatment, will produce wastewater suitable for any reuse, except of course direct consumption, so-called toilet to tap. That’s still illegal in California, Mimiaga said. But the water is good for the City’s plans, which involve piping back the recycled water to an injection well field located on the power plant property. There the water will be injected into the underground Morro Creek aquifer to bolster the supply and throw up a block against seawater intrusion. The Morro Creek wells, located on the east side of Lila Keiser Park, would then pump out the mixture of normal groundwater and the recycled water, and run it through the City’s desalination plant before piping it up to the Kings Street tank farm and blending it with the City’s other sources for delivery all over town.

The plant is spotless, as Mimiaga leads the way through the front gates on a paved road leading through the plant.

The new Administration Building is the first structure one encounters, with a big American Flag waving on a pole by the entrance. The outside has the feel of a new car, but inside it’s a different story.

Mimiaga asks for forgiveness for the condition of the building, which sustained major flooding damage several weeks ago, when on a weekend, a water pipe burst and flooded the entire building, with clean water.

The drywall became soaked and to prevent mold, is being removed and rehung with clean wallboard. The walls are marked with words like “Demo” and instructions to remove cabinets in one small room so the drywall can be removed. It must truly have been quite a mess, but Mimiaga said readers should not fret, because the contractors, Filanc/Black & Veatch, will pay for the clean up and repairs.

Outside he points out two large canopies under which the department’s vehicles and other large equipment will be stored. A large water tank looms behind. It’s one of the main tanks in the recycling process, Mimiaga said.

The raw sewage will enter the plant and be piped all the way to the far end, where the treatment process begins with screening out inorganics in the waste stream, a process collectively called “gritting.”

Mimiaga explained that there are a series of increasingly finer screens that sift the incoming raw sewage, removing all the things that people flush down toilets. “You’d be surprised,” he said. The fine screen strainer is, “like a spaghetti strainer on a drum,” he said, “This is one of the most important pieces of equipment. Any inorganic materials would be damaging to our membranes.”

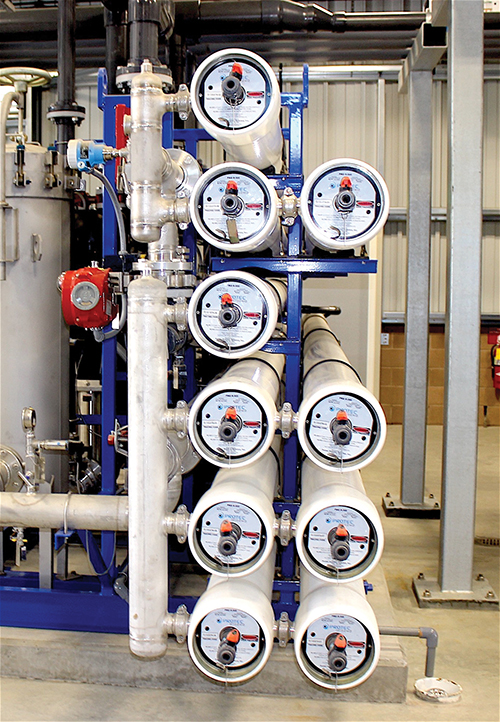

The wastewater, now called “black water” for obvious reasons, is sent through a second process involving a well filled with fine screening membranes. The wastewater floods the well and pumps suck the water through the membranes, filtering out the smallest of solids in the process.

Once through the membrane reactor, the water is piped into an “activated sludge Pond” a deep pool of water where the biological portion of the process takes place. “It’s the biggest tank on site,” he said of the two bioreactors with the City expected to just run one side at a time. The activated sludge is actually a culture of microorganisms, which eat the remaining organic wastes in the water. Big compressors — called Bubblers — aerate the sludge ponds constantly feeding the little critters oxygen to keep them healthy.

On this day the pool is full of what looks like pool water, a greenish-blue that might be inviting on a hot day. But when the plant is running, the water will be a chocolaty brown, and definitely not something one would want to dive into.

The sludge is the key component in this MBR process. They will have to bring in a live culture from somewhere else, Mimiaga said, possibly a treatment plant in Paso Robles, and grow their own cultures for each tank. “They eat raw sewage,” Mimiaga said, “and we harvest their dead bodies. That’s how we remove the solids.”

The sludge is drained away daily and sent to a series of deep pits, where it will collect until it’s put through a dewatering process, essentially a large conveyor belt that lays out the sludge flat and sends it through a series of rollers, squeezing it more with each turn until the dried sludge is dumped into a container. That will be trucked to the Central Valley where it will be used for fertilizer, he explained.

Once the water leaves the sludge pond, it splits, Mimiaga explained.

Some of the wastewater is sent to chlorination tanks, and then de-chlorination tanks before being piped back to town for discharge into the ocean, using the City’s old desal plant discharge that dumps into the canal at the base of Morro Rock.

The rest of the water is destined for a separate process to make it recyclable.

The recycled water is disinfected using ultraviolet light and then sent through a full reverse osmosis plant and calcite is added to control the acidity. It’s then piped back to the injection wells at the power plant.

That recycled water, “is highly regulated, sampled and tested every day,” Mimiaga said. He added that ironically, when the water is pumped out again it goes through another RO process along with the Morro Creek groundwater. “It’ll be pulled out and treated again,” he said, adding that the water that is going to be injected into the ground is cleaner than the natural groundwater, which the City has documented, is high in nitrates. “It should improve the quality of the groundwater table,” he said.

He noted that now the recycled water is thought of more as an insurance policy, but in the future could be called upon to provide more and more of the potable water. As for the overall project, he said the conveyance system is 90% done and segments are being pressure tested. They should have power to the two new lift stations within the next week or two, depending on PG&E’s schedule.

He said they are testing the pipes with drinking water too. They are on a tight schedule at this point.

They’ve set a target date of Oct. 4 for when raw sewage will start being sent to the new plant. “When we introduce raw sewage,” he said, “then we’ll have a functioning wastewater treatment plant at that point.”

He said the City has s few months left in its time schedule as ordered by the Regional Water Quality Control Board, under the City’s discharge permit.

The City has a three months waiver before the discharge regulations kick in. We should be fully compliant within a few days. Oct. 4 is a big day here.”

The water board ordered the City back in 2003 to bring the old sewer plant up to full secondary treatment standards, in order to eliminate a so-called 301(h) permit under the Clean Water Act. That permit allowed the plant to discharge a mix of primary and secondary treated wastewater, an occasion that only happened a few times a year when Morro Bay and Cayucos flow is too high for full secondary.

Over the past two years the project has been underway, cost overruns have been concerning for just about everyone in town who pays a water and sewer bill.

He said they are at $76 million for the plant at this point. The original contract was for $69 million. “The City started this with an estimate of $126 million,” he said. The project will likely go about $33 million over estimates, but he points out that the financing came in so low — both a State and Federal loan have interest rates under 1% — that the savings has been enough to cover the overruns and spare any rate hikes.

Mimiaga, after explaining the intricate and extensive control systems and backups, and the countless miles of wiring and conduit that went into the plant, said, “It took about 50 men two years to build,” he said, while also marveling at the genius of electricians who wired the whole thing together.

And as for the large dirt parking area where the project has staged its construction trailers and where workers parked, it is not part of the plant site. It’s owned by the “Shepherd and Seashell Properties” and includes a small subdivision on Teresa Drive. Under the lease agreement and required by the permit, it must be returned to grasslands when the project is done.

The owners have asked the City to include the property into its sphere of influence in advance of a future annexation. They have also asked the City to change the zoning to allow smaller buildable lots and greatly increase the allowable units.

Mimiaga said the City may plan a grand opening sometime in the future, to allow the people who are paying for it to check out the largest infrastructure investment the town has ever seen.